Virtual learning didn’t kill school system; it made flaws visible

Why are so many students who, for the first time in numbers that stagger even the most faithful supporters of our school system, failing in school in the United States? This question has become increasingly poignant with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, abruptly changing the immediate lives of millions across the U.S. Moreover, are these students failing, or are the teachers failing to teach the students, or are the school districts failing to adapt educational procedures and policies that facilitate learning in the 21st Century? To paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, “when in the course of human events[,]” it has become necessary to rethink the approach to how students are taught in schools.

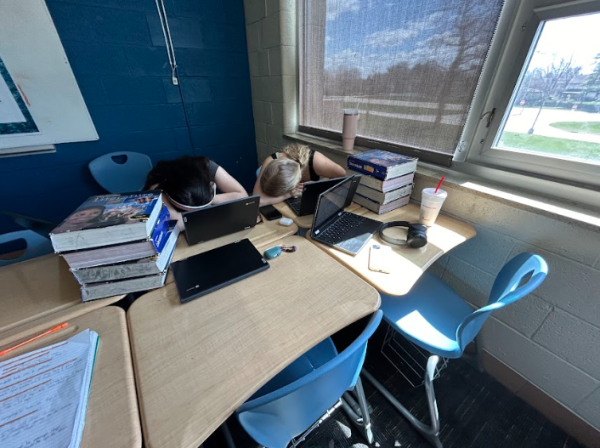

The agricultural-approach that enabled farm children to be home during the summer to work the fields remains one of the archaic approaches to education in the United States. To be sure, with the overwhelming prevalence of the COVID-19 pandemic in American life, such an outdated inadequacy of the educational system has become more conspicuous. The focus of school districts must finally juxtapose the need for obtaining knowledge with the prevalence of computers and the immediate access to an array of information via the Internet, with the critical thinking skills necessary to evaluate this information, its sources, and its importance in public education. Even how students are being taught requires new schooling approaches in light of students failing during virtual learning. More specifically, the emphasis on grades and grading, the standardizing of curriculums, and the trend of replacing face-to-face instruction, need to be reevaluated because of the inadequacies of virtual learning.

The Rockford 205 District, along with school districts across the country, report a larger number of students who are failing and many who have no academic history of failing in school, as demonstrated by the recent change in schedule from two-day active remote learning to five days active remote learning, giving most students hardly time to adapt. RPS 205 has made virtual online learning technologically possible by helping disadvantaged students gain viable Internet access via Comcast and loaning adequate laptops for home. Even so, educators still have to reexamine possible inadequacies of online teaching and learning. These failures of virtual learning should force teachers and administrators to conclude that grades and the grading systems have become as archaic as summers-free for the sole purpose of farm children working the fields. If grades and the inevitable delays in teacher grading of a student’s effort can be deemed in the best interest of the student, why are so many students, for the first time, failing?

The standardizing of curriculums appears, at first, as a viable solution to ensure consistent learning and academic achievement. Most public school districts have adopted the Common Core curriculum as an approach to educating their students. Often, this approach has led to a plethora of mundane handouts (the busywork that so plagues virtual learning) and ‘robotic’ teaching by faculties nationwide. Control over the curriculum no longer resides in the purview of the teachers who are told not only what to teach, but rather through the methods of centralized government bureaucracy, how to teach. Teachers, trained to respond and adjust their teaching techniques to the different learning abilities of their students, have typically shifted away from actual one-on-one instruction and interaction to an approach that awards performance on a standardized test. However, when used pedagogically in a virtual learning environment, such an assembly-line approach to teaching a standardized curriculum reveals how inadequate it truly is. With such a vast array of information immediately available via the Internet, available without time-consuming research, who should decide what information should be accessed and reviewed by students?

Since the advent of new audio and video technologies in schools, districts nationwide have tried to adopt such new technologies to the classroom, in effect, as ways to eliminate the need for actual face-to-face instruction and reduce instructional costs. With the proliferation of computers and access to the Internet via meta-search engines, school districts are looking at virtual or distance-learning as viable instructional approaches to instruction. Even a precursory look at the results during this pandemic reveals the inadequacies of such an all-inclusive, ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. Some students just do not learn at a distance without a teacher’s trained observations of each student’s, often unique, learning skills and learning disabilities. The adage that not all students learn the same way at the same rate has become more vivid in the virtual classroom today. It is only by the willingness of the teachers of this county to take back control of their classrooms from government-sanctioned district ‘one-size-fits-all’ standardized bureaucracy and teach their students however they see most beneficial for their students will we see an end to the seemingly insurmountable educational troubles our nation’s students routinely face on a daily basis.

Perhaps the one and only positive to come from the pandemic in the U.S. has been how the inadequacies of distant and virtual learning revealed how the archaic emphasis on grades and grading, the use of government-sanctioned standardized curriculums, and the learning environment shifted away from teachers being able to effectively teach their students. By simply dissolving and replacing this inefficient and destructive bureaucratic nightmare of a system, RPS 205 and its superintendent must eventually come to know the only answer to this problem is to dissolve and radically reform the system they choose to use despite how oppressive it has now become to students simply seeking a decent education in the 21st century.